Idea Development

For my final project proposal I had to come up with three concepts for either a short story or a collection of poems, all which had to link back to Sylvia Plath or Edgard Allan Poe in one way or another. Before anything, I began by brainstorming some of my ideas on paper; briefly breaking down their plot points, themes and how they relate to confessionalism.

After outlining a few ideas, I picked four of my favorites from the bunch to further develop for my pitch:

- ‘The Foxes Always Scream at Night’

My first idea is a psychological, short horror story that follows a student’s descent into hellish night after they witness the corpse of a fox move. The main themes I want to explore through this short story heavily relate to mental health, specifically insomnia and ‘late night’ anxieties as these are issues personal to me. Naturally, this concept is also influenced by the gothic genre (in terms of the dread and tension I aim to create) and Poe’s works.

- ‘Rat Catcher’

This is another horror short story (a recurring theme in my work) that revolves around a writer’s investigation into a strange clicking sound coming from within the walls of their home. This story is intended to be an allegory for creative blocks and the difficulties some artists face when it comes to starting new projects, a problem that I struggle with myself.

- ‘The Spider of Watkin Manor’

Rather than a short story, this is a poem told from the perspective of a spider as they witness the sinister goings on of Watkin manor. Just like my previous ideas, this will feature horror elements akin to the Edgar Allan Poe’s: The Raven.

- ‘Eyes’

Another poem, ‘Eyes’ is a story told in the form of a panicked account as the speaker outlines the last week of their life and how they believe that they are being followed by supernatural entities – evoking baser, paranoid fears.

Out of these ideas I chose three for my final pitch: ‘The Foxes Always Scream at Night’ and both of the poems. Even though I was excited about my ideas for ‘Rat Catcher’ it ultimately felt less developed than my other short story and I only wanted to use one for the presentation.

Inspiration and Research:

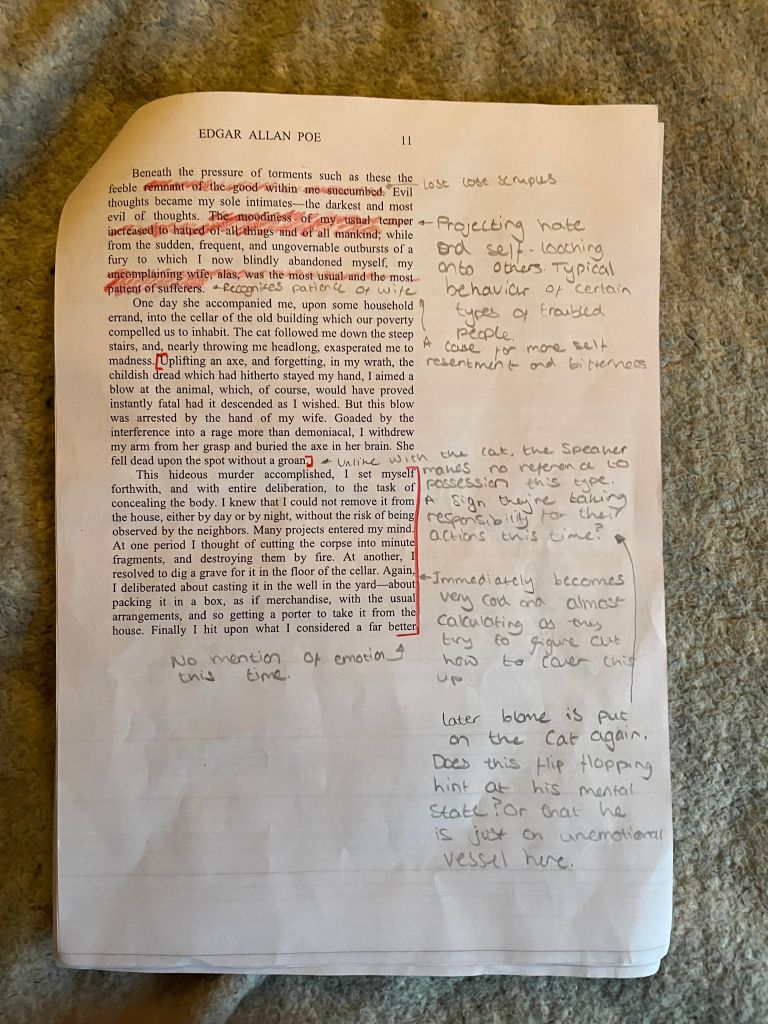

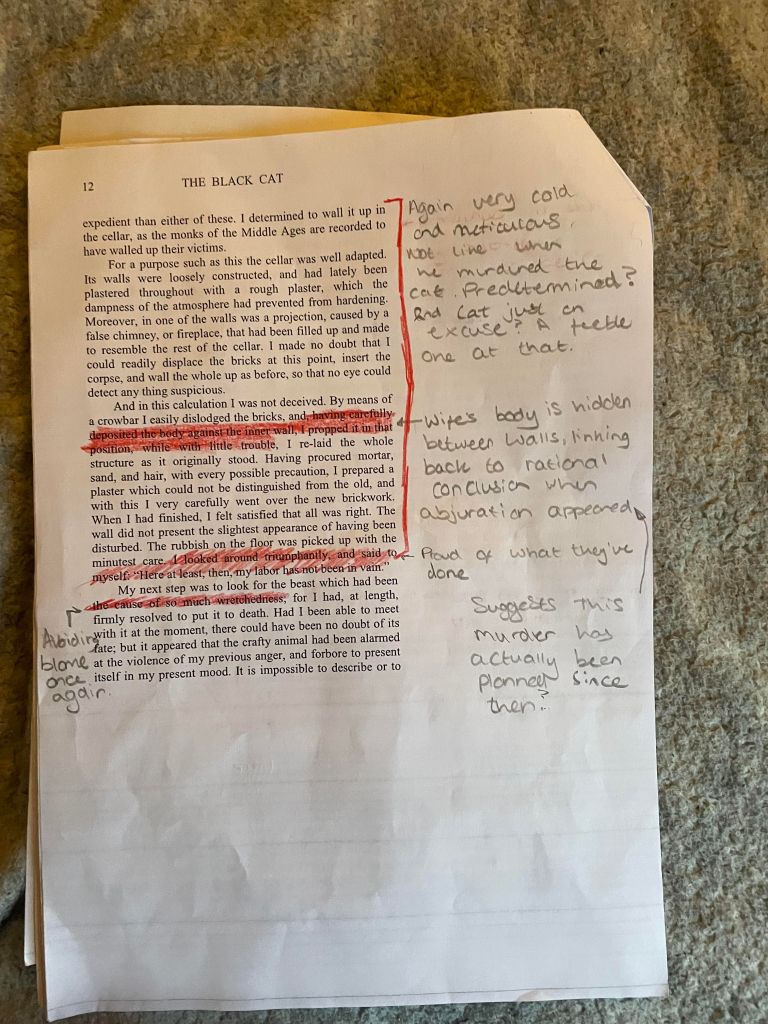

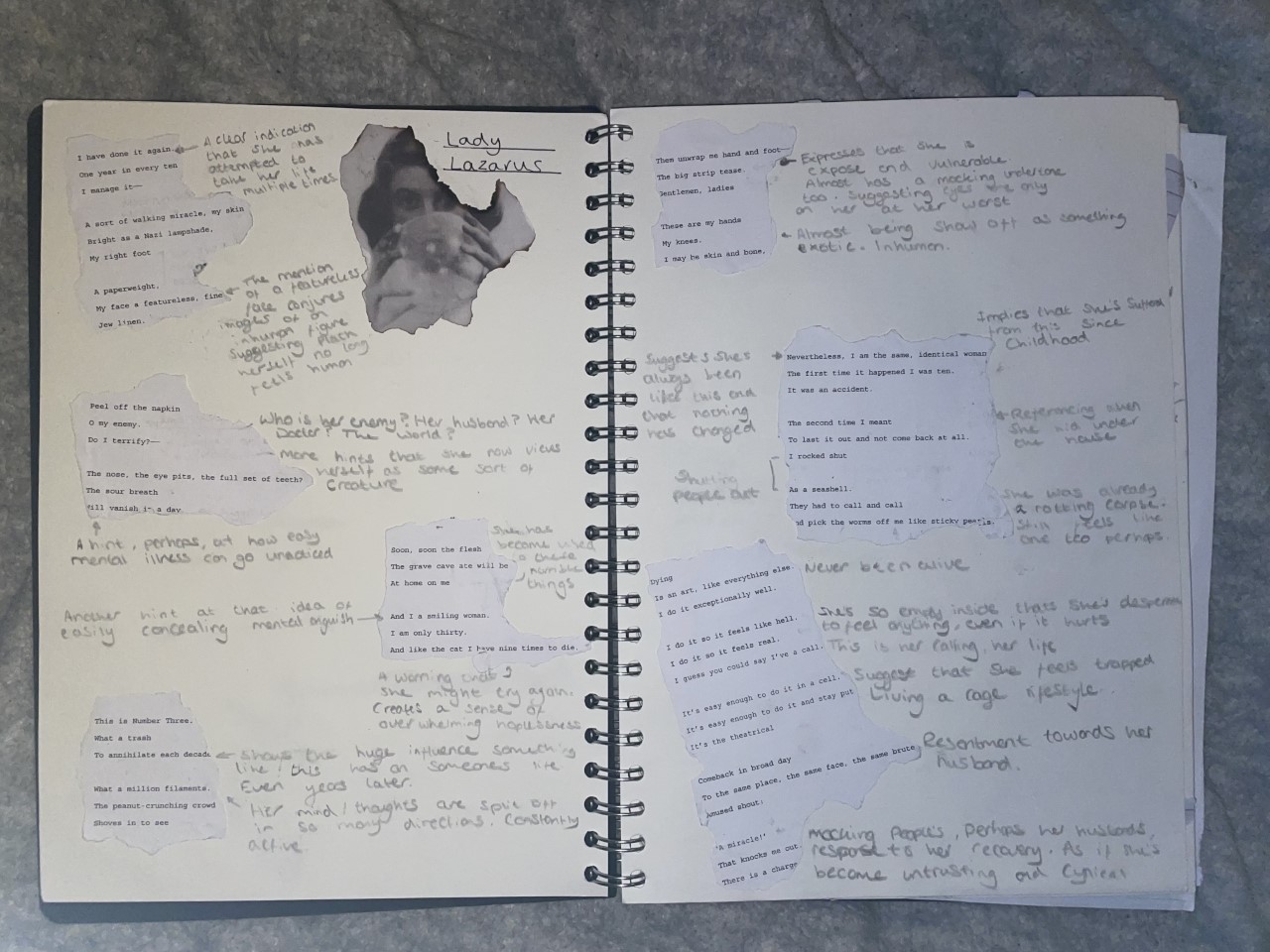

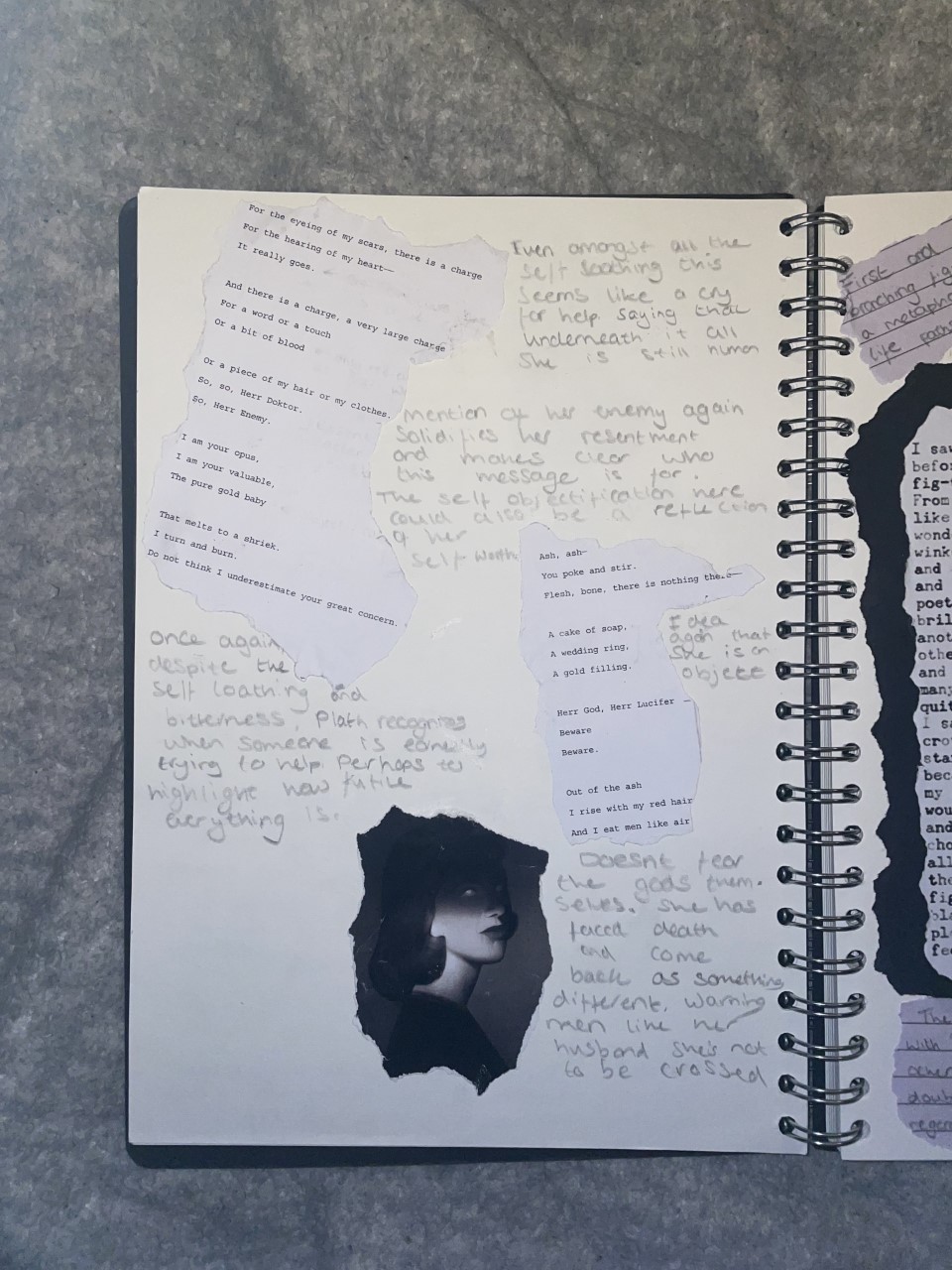

As mentioned previously, these concepts all link to Sylvia Plath and Edgar Allen Poe as their approaches to confessionalism and catharsis inspired parts of my work. I found myself particularly interested with Poe writing due to its gothic and horror influences, genres that I am particularly interested in. However, Plath’s emphasis on mental health is something that I can personally relate with and, as a result, is something that I have also attempted to integrate into my work. So in preparation for my pitch, I went back to my earlier work analysing the writers’ texts – refreshing myself of some of their art and what made them so effective.

However, during this process I also found inspiration from other writers such as Stephen King and Emily Carrol, who have both created their own anthologies of horror stories. Their work is some of my favourite in the genre and helped me better understand how to craft effective horror and translate it to a short story format.

Another source of inspiration came from a different medium entirely. The video game, Dishonoured: Death of the Outsider, features a mechanic that allows players to communicate with rats, wherein they give players tidbits of information that can aid them in their tasks. This sparked my idea to write a creative piece from the point of view of a some sort of verminous creature, which eventually became ‘The Spider of Watkin Manor’.

Finally, some of my real life experiences have also inspired these concepts. Fortunately I haven’t had any interactions with talking spiders or supernatural entities, but simple everyday occurrences have snowballed into grander ideas – similarly to what happened when I came up with ‘The spider of Watkin Manor.’ One of the most prominent examples is how I came up with ‘The Foxes Always Scream at Night,’ as the trilling of foxes is something that I would often hear on the nights I was struggling with insomnia. The association of these two things helped form the supernatural foundation for my short story’s horror elements.

Zine:

When thinking about the actual format and medium of these short stories and poems, I plan on presenting them in the zine format by combining my writing with various illustrations relevant to the stories’ contents. For example, in ‘The Foxes Always Scream at Night’ I could include a fox on each page that slowly becomes more decrepit as the story goes on. I want to create these drawings myself, similarly to what I did when creating a post for my writing instagram page:

After completing my research and finishing the overviews for each concept, I compiled different parts of my notes in a powerpoint for the pitch:

Reflection

Rationale:

During my pitch, most of the questions I received were related to my short story rather than my poems – leading me to believe that was where most of the interest lay. Naturally, this has influenced my decision on what idea to go with for my final project as it appears the concept of my poems might not have been as intriguing as my short story. However some of these questions were asked with the purpose of clarifying, what seemed to be, slightly confusing aspects of my pitch – which might be telling of my presentation skills rather than the quality of the ideas themselves.

Concept:

Based on the feedback I received from the presentation and my overall confidence with the story when compared to the others, the concept I have chosen to pursue further is “The Foxes Always Scream At Night.” With this story I would also be writing in traditional, a style that I feel I am more skilled at than poetry.

Evaluation:

I found the preparation for my presentation to be a beneficial task as It gave me an opportunity to get various ideas onto paper before tightening them up and developing them further. However, I feel that the organisation of the notes I took during this process could have been neater as, looking back on them now, I can see how they might seem confusing. I believe that this is an issue that affected my presentation directly since, as mentioned previously, I had to clarify some of my ideas.

This however might have also been thanks to my general speaking skills as I found actually presenting my ideas to be a nerve wracking experience. In the future I think I could benefit from creating myself a script beforehand, so that I am not just reading from a powerpoint. Speaking of, I didn’t include a slide on zines which as a result meant I had to improvise what I wanted to say about them on the spot. For future projects, I will ensure that I am fully prepared and check that I have met all the requirements of whatever task I may be working on.

I was satisfied with the layout of my powerpoint, as I think that it was neat and aesthetically matched the tone of the concepts I presented. Though I am only further developing one of them, I am mostly confident in the rest of my concepts and hope to pursue them as well at some point in the future.

Bibliography:

- Full Dark, No stars and The Bazaar of Bad dreams, by Stephen King

- Through The Woods, by Emily Carroll

- The Black Cat and The Raven, by Edgar Allen Poe

- Insomniac, by Sylvia Plath

- Dishonoured: Death of the Outsider (2017), a game from Arkane Studios